Author: moaz

-

The Essay is A Kind of Fieldwork

Duration is a form of knowledge – it is not an obstacle to progress. Of course I say that, my last essay that I made public was in February of 2024. And 14 months later I am all the better for it. 2024 was a year of questioning. It was a year of answers. It…

-

Dreamscape – collection 1

This collection is part of “The Worlds to Come” – an ongoing multimodal study of Islamic mythology: miracles, dreams, and the supernatural.

-

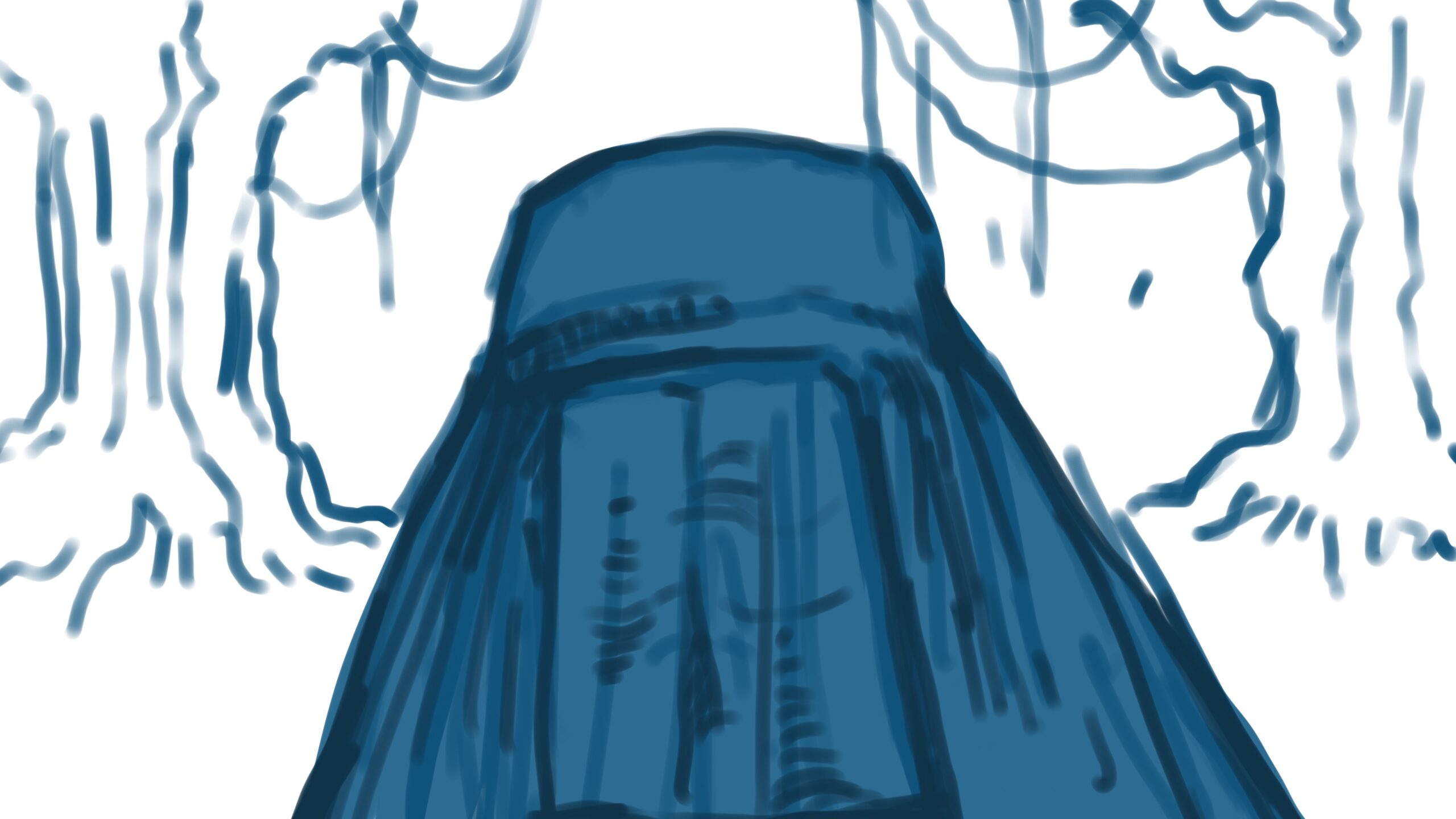

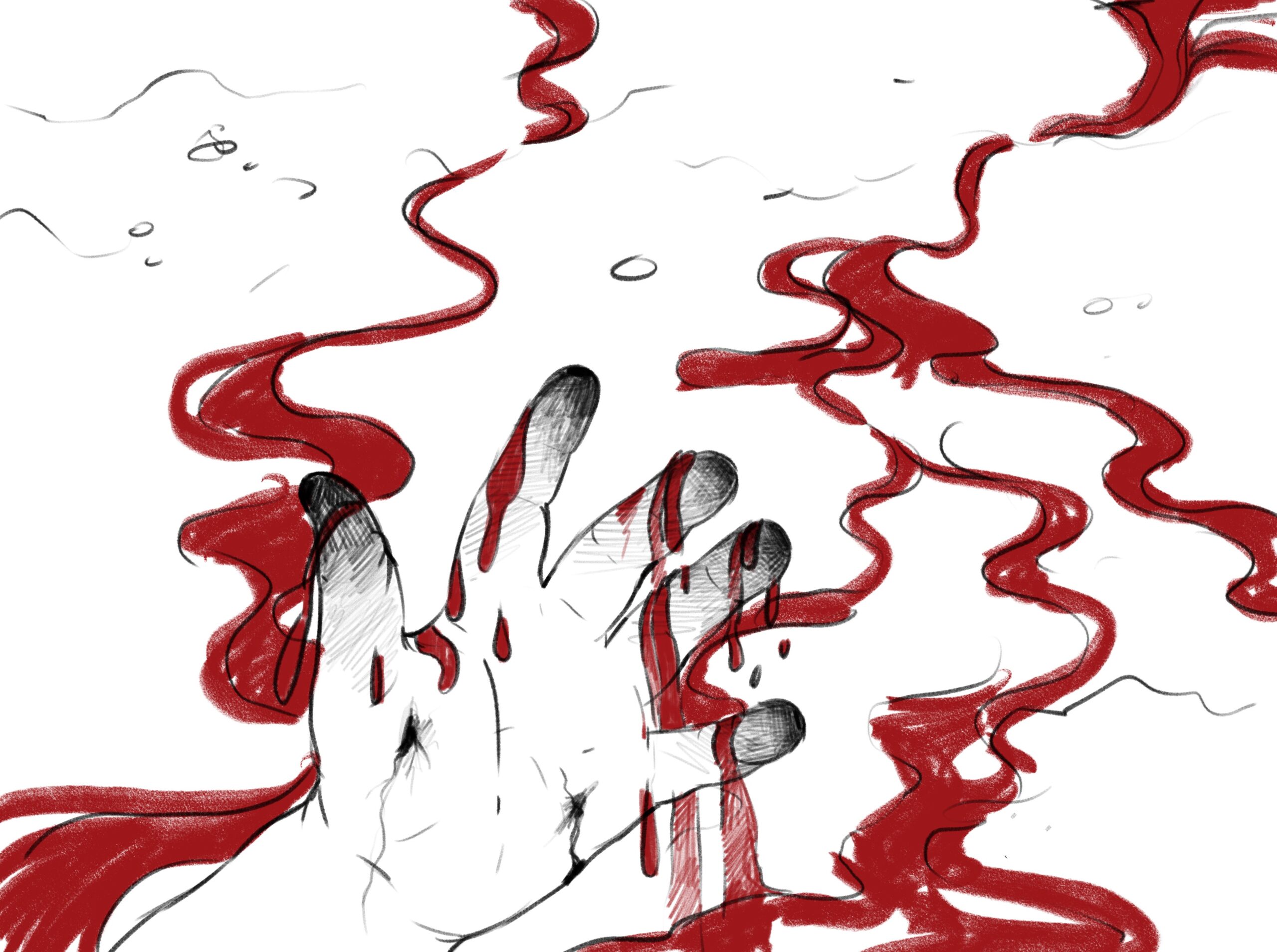

Miracle-observation-2

These sketches are part of an ongoing visual exploration of Shia social memory, ritualistic thought and identity, through investigating miracles, dreams, and super natural encounters from the beyond. Sketch: 10th Muharram 61 AH – Sakina and the blood of Banu Hashim, the Prophet Muhammad’s clan, mixing in the scorching sand of Karbala. Sketch: The tasbeeh…

-

Lately just wanna fly

Lately just wanna fly. I need to be everywhere and do everything and know everyone. But as soon as I get there and do everything and know everyone I need to be everywhere else and do everything else and know everyone else. It never stops. I may finally be coming to the stone cold realization…

-

From oceans of Light

Among Shia works of the Safavid era, Baqir Majlisi’s writings (his most popular work is the Bihar al Anwar, 10th century collection of Ahadis) on Karbala are characterized by an insistence on the predestinarian quality of Imam Hussain’s sacrifice. In the chapter “The ways in Which God informed his Prophets of the forthcoming martyrdom of…

-

Miracle-observation-1

A shabeeh (replica or mimic) Zuljennah – the horse of Imam Hussain – surrounded by mirrors. Inspired by the tradition from Mubarak Haveli in Mochi Gate Lahore, where each year before the Ashura procession on the eve of 9th Muharram, the horse is shown a mirror in order to reveal the stature or depth of…

-

My Illusion of Stability

There’s mustard growing in the garden of the new house I just moved into. There’s also spinach, mint, radish, green beans, some variation of coriander or cilantro. Every morning, mere eggs at breakfast are now insufficient until one or more of the fresh greens are plucked from the garden and added to the mix. Usually,…

-

Protected: Of man and Legend

There is no excerpt because this is a protected post.

-

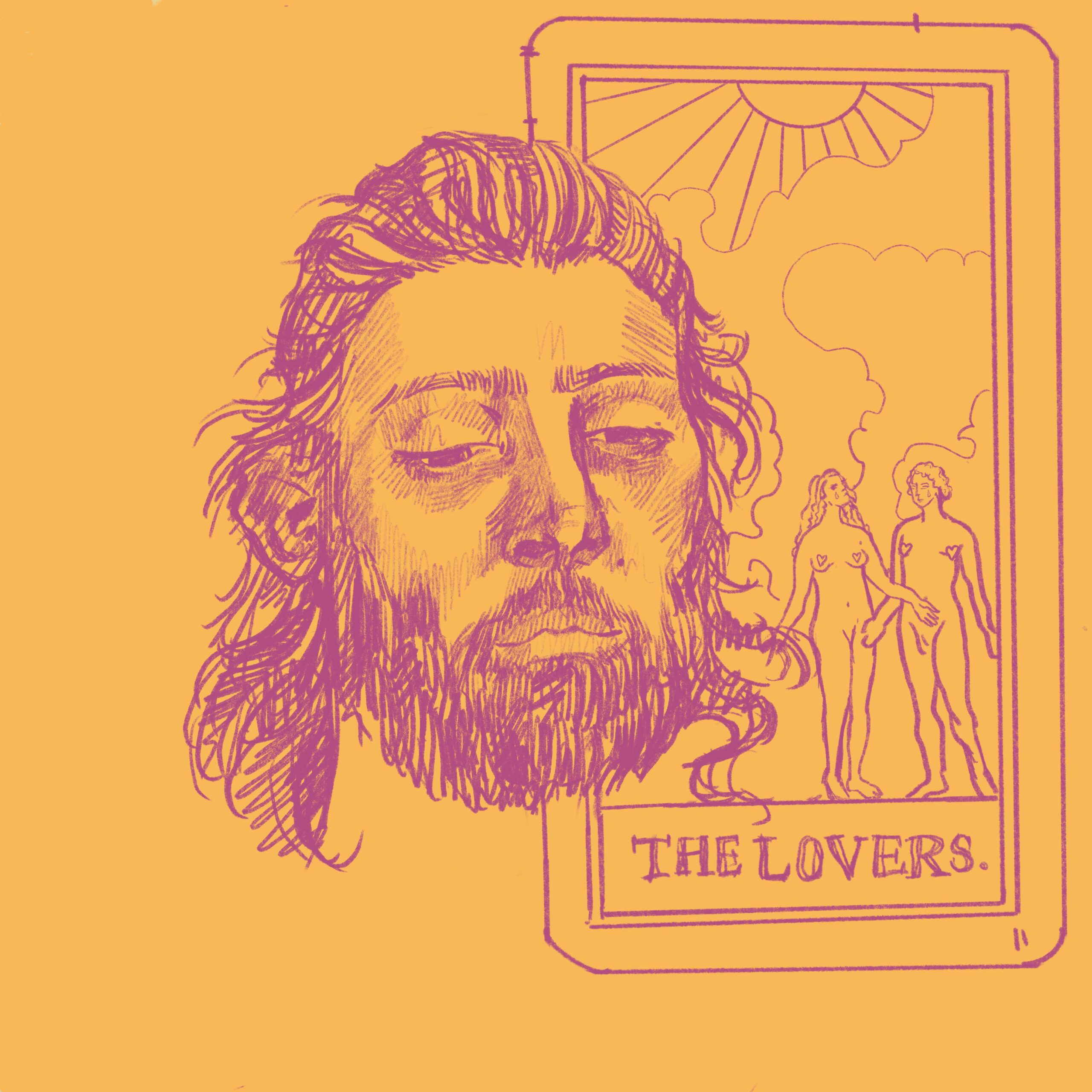

Hussain is escorted from Karbala

Not far from the bank of the Euphrates, a child not older than 12 sits solitary in scorching desert sand with her legs crossed. Her head is uncovered, bare under the orange sky, for the very first time. Behind her, a dozen tents are set ablaze. She can feel the heat on her back –…

-

Jinns of Mochi

Clamor and sweat, commotion and suffocation, uproar and eruption. For the past three years I have found myself among these sensualities in the Mochi Gate area of Lahore, in the late hours of 9th Muharram. When I was a child and oblivious to the practice of Hussainism, my mother would often bring up the mention…

-

Tea is a love language

When I was growing up my grandmother used to tell me the story of a friend of hers who used to offer chaye in such a reluctant and uninviting manner that no guest of hers would ever leave dignified. It was always a funny bit to me. In our big cities, there are only a…

-

How Lahore is/feels..

Between the camera shops on Lahore’s Nisbat Road, lies a tiny chaye wala dhaaba. Back in the day when we frequented the area looking for gear upgrades or to pick up prints or just to be out and about, the dhaaba was on the top of my list of essential stops to be made. The…