Monthly Archives: January 2024

Hussain is escorted from Karbala

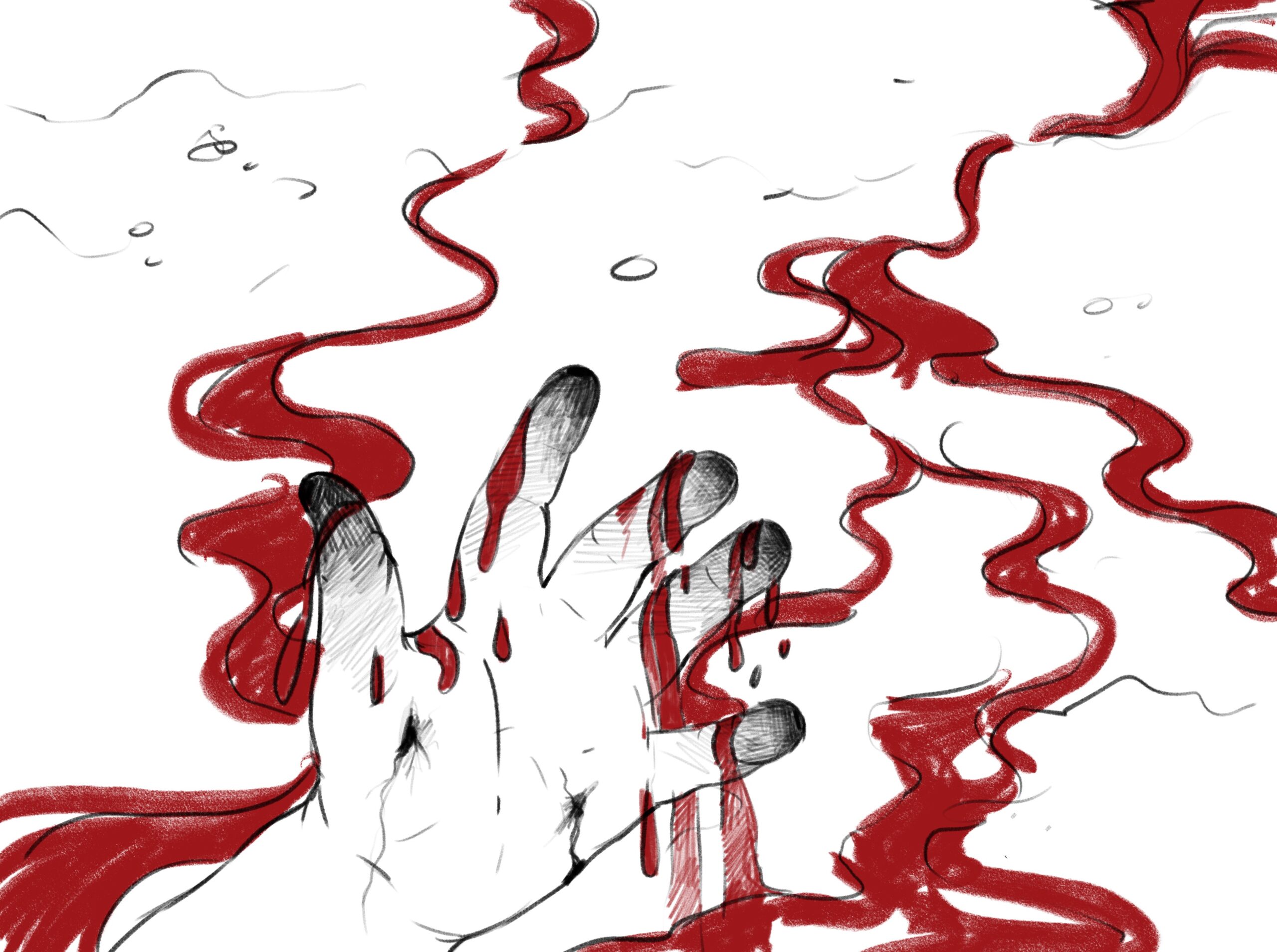

Not far from the bank of the Euphrates, a child not older than 12 sits solitary in scorching desert sand with her legs crossed. Her head is uncovered, bare under the orange sky, for the very first time. Behind her, a dozen tents are set ablaze. She can feel the heat on her back – the sound of crackling embers and murmuring flames speak of those she set out of home with – but those she can’t find by her side in Karbala anymore. Those who are now fell. Her brothers, her uncles, her kin. Her father. At some distance she can see him – he’s turning into a mirage. Within an arm’s length she can feel him to be at times, but eons away when she reaches out for his embrace. Tall, burly figure. An imamah on his head that was once green, like the one his grandfather used to wear in Medina. But Sakina’s father’s imamah has turned red from all the blood. His broad back is overwhelmed, bent from all the arrows and spears. From where she is sitting in the sand, she is unable to count the number of wounds that are visible on her father’s body. But the blood dripping from his body has made its way through the sand, to where she is sitting.

Sakina reaches out cautiously – this is her great-grandfather Muhammad’s blood, she thinks. The blood of the Seal of the Prophets. A legend comes to Sakina’s mind – the story of Gabriel appearing in the desert when an infant Muhammad was in the care of his foster-mother. Sakina is transported from the burning afternoon sun of Karbala to the cool night sky in the outskirts of Makkah. She can see Gabriel cleansing her great-grandfather’s heart in the dark of the night with Zamzam, and then sealing it back in its place inside Muhammad’s chest. This is the same blood, Sakina reminds herself as the tips of her bruised and withered fingers make contact with the blood of Hussain in the boiling heat of Karbala.

This is her grandfather Ali’s blood, she thinks. Muhammad’s brother, Waseeh, Allah’s Wali. The fountainhead of Muhammad’s progeny. A legend comes to Sakina’s mind; the remarkable story of Ali’s sword, Zulfiqar. When in battle, the Zulfiqar could tell who it was in combat against. It was said that even if a single person from the progeny of the Zulfiqar’s opponent had a Muslim Momin believer of Allah and Muhammad, Ali’s sword would not make the kill, would not shed blood. And muslims have now shed the blood of Hussain, the blood of Ali, the blood of Muhammad, Sakina thinks. She gently places her hand on the ground. The time for Hussain’s final Asr prayer has long passed. Strong winds from the east blow dust over the fallen bodies of Sakina’s family, sprawled across the desert. She becomes a little perplexed at a strange but brilliant glow rising over the horizon. Four illuminated figures surround Sakina’s father.

Hussain’s escorts are here, she tells herself.

Above her, the sky splits into two.

Beneath her, Hussain’s blood has forever exhilarated the earth.

Jinns of Mochi

Clamor and sweat, commotion and suffocation, uproar and eruption. For the past three years I have found myself among these sensualities in the Mochi Gate area of Lahore, in the late hours of 9th Muharram.

When I was a child and oblivious to the practice of Hussainism, my mother would often bring up the mention of the processions of Mochi Gate, and the legend of supernatural forces (Jinna’at/spirits) participating, even assisting, in the tumultuous traditions that took place in those exceedingly crammed streets. The legend is simple (hah): there are jinna’at present among the overcrowded rallies, hovering overhead and assisting in carrying the heavy tabuts and shabeehs. Their bodiless forms racing from end to end invigorating the frail humans below to not succumb to the daunting physical aspect that is part of these rituals.

However, the Shia sensibilities I grew up in were always rather moderate and this new year, I am yet to step foot inside a Muharram procession and chances are I will not. Sitting here at home binging majalis on Youtube, spending time in prayer and remembrance, my spirit is well-fed. Yet now after all, I can feel the so-called supernatural, most-likely made up jinna’at of Mochi Gate creeping up behind me, calling my body to be physically present amidst the chaos in those streets. Amidst chants, thumping chests, a sudden stampede when a Zuljanah is passing through. Langar at every doorstep. All night long until a unique Fajar azaan is sounded, and with it, the dawn of the battle.

Four times Allahu Akbar resonates within the narrow streets of Mochi as it did in the barren desert of Karbala, and thousands of souls, supernatural and human, erupt into a wail. The air is filled with sheer stupor. Then the shahada of Tauheed, and somewhere in Karbala swords are taken out of their sheaths. The shahada of Risalat, and archers ready their bows for the Rasool’s grandson. So on and so forth, until all hell breaks loose.

I don’t know if I believe in the jinna’at of Mochi but if there is anything that can elevate our finite humanness into a form beyond comprehension, it is Hussain’s defiance. His “La”, the very root of Tauheed.