Duration is a form of knowledge – it is not an obstacle to progress. Of course I say that, my last essay that I made public was in February of 2024. And 14 months later I am all the better for it. 2024 was a year of questioning. It was a year of answers. It was a year of regrets. It was the year of mammoth, alien love. An impossible, towering thing. 2024 was the year new dreamworlds revealed themselves to me, were spilled into me. Spilled out of me. All at once leaving me welcomed and wary. It was the year I played chasing tails with my own shadow. We have since arrived at an (uneasy) truce. But there are other shadows I chase still – not all of them mine. This is an essay about writing essays about that which was never built for arrival. About a stitching together of fragments, about recountings of fleeting atmospheres. Unhurried conditions and unfinished moods. They move through me now without asking for permission, these shadows. Some are inherited through relentless remembrance of that which refuses to resolve. Others disguise themselves as clarity and yet resist naming. They linger slowly in rituals, soaking up tenderness from the material. As I melee my way through the notes for this essay, I see that parts of it were compiled with the ambition to become a New Year’s essay. But that shape of work, evidently, was met with staunch refusal. It asked not to be concluded, only continued. Not so much as a reflection but rather, a recursion. A looping back that seemed to have changed each time I returned to it. And so this – this became the method. To dwell in the unfinished. To let the work arrive late, or not at all.

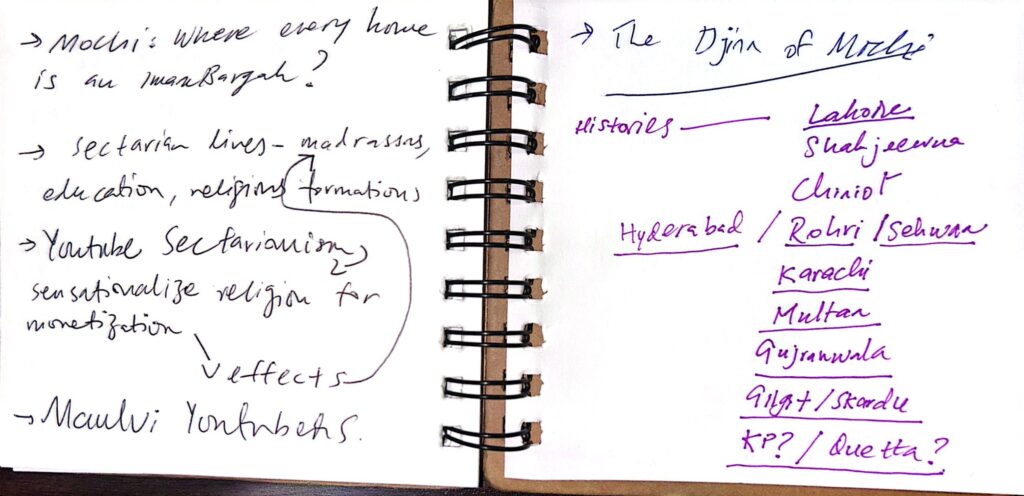

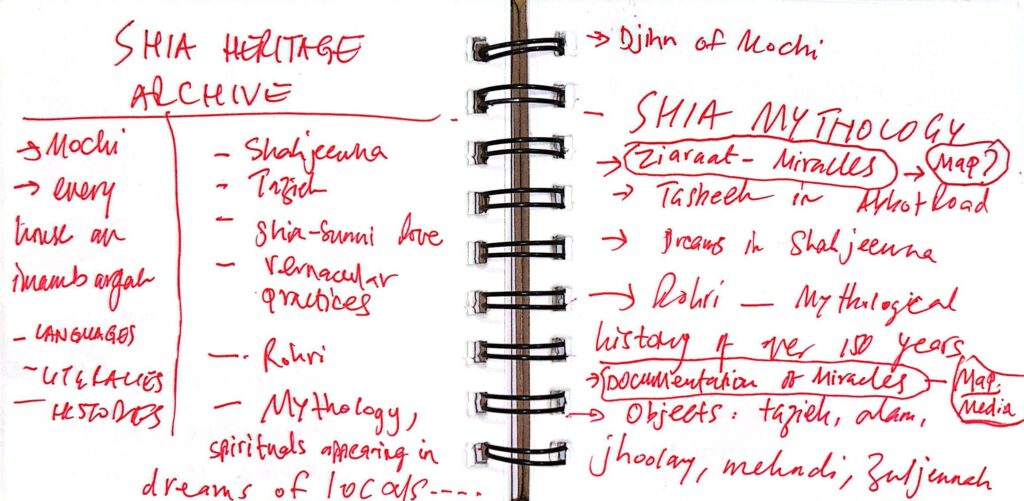

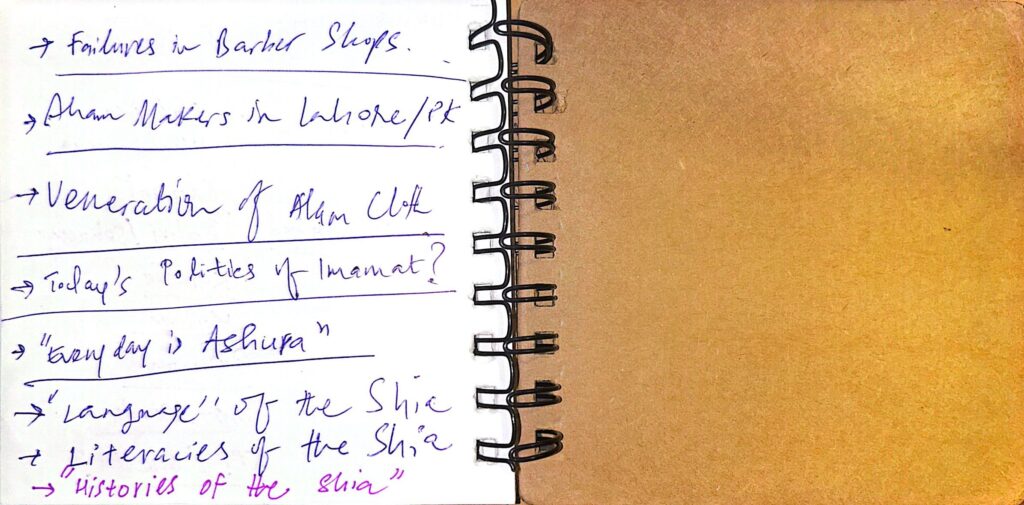

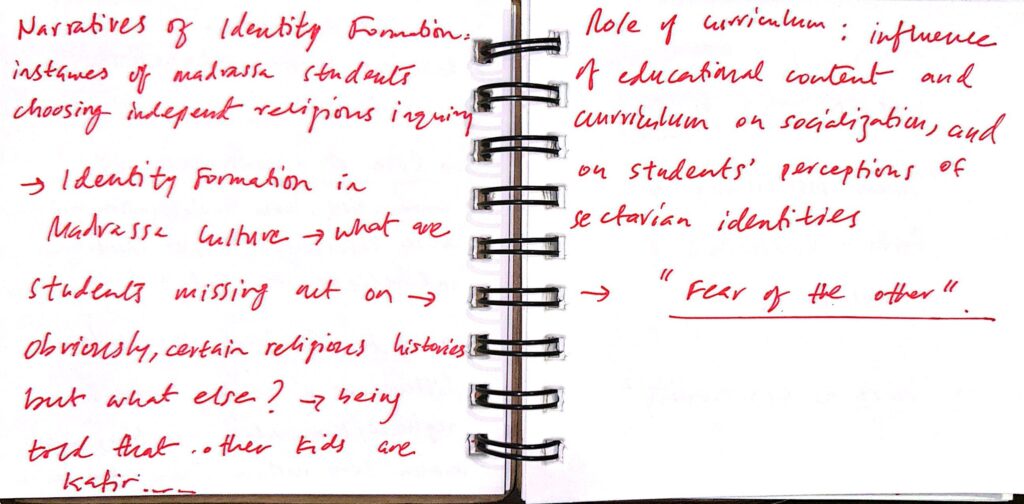

This is an essay about writing essays about a centuries old world (albeit it omits, for now, the rituals of gatekeeping these essays)—aworld that began revealing itself to me not through mastery, but through upheaval. Through unprecedented unlearning. In December of 2023, I entered the Pakistan Photo Festival Fellowship as a documentary photographer, with nearly a decade and a half of orbiting Shia spaces of remembrance in Pakistan—recording, preserving, consuming, and occasionally publishing what I understood, then, to be “work.” I arrived already steeped in archives, worn with familiarity. But by the fourth week of the workshop, as I struggled to articulate what newness I could offer, a close friend asked me to look away from it all. To start over. I took the suggestion seriously, if not easily. So then, quite conclusively it seemed, I decided I wanted to trace a quiet cultural shift I had observed among young Pakistanis: the decentralization of religious authority through platforms like YouTube and TikTok. I was interested in how virtual accessibility to sermons, ziyarats, and sacred histories was opening pathways for self-led inquiry—how it was loosening the grip of sectarian politics and allowing many to return, with fresh eyes, to the histories, spiritualities and memory once withheld from them.

At the time, I believed I was turning outward. Stretching myself toward new horizons, new tools, new communities. But the truth was far less linear, and far more intimate. I wasn’t meant to look further—I was meant to look deeper. What I had mistaken for the edges of the archive were merely its thresholds. The world I had spent years documenting had been holding its breath, waiting for me to arrive differently. And when I did—when I slowed down, when I stopped treating the unseen as metaphor, when I allowed what had once been left outside the frame to guide the frame itself—it began to open. Not with spectacle, but with silence. With dreams, with whispers, with refusals. I wasn’t discovering a new world. I was being returned to the same one, layered and saturated, its unseen dimensions rising up to meet me.

As “A World Unseen” began to take shape – if shape is even the word – I found myself unable to make it fit inside the frame of a typical documentary or photojournalism project. For years I had moved through the documentary image like a loyal cartographer: documenting, captioning, compressing meaning into something legible, reproducible. I have always known how to tell a story. Dress it up, pitch it clean. To me the architecture of legibility is second nature, in ways. But something about this moment asked for a different grammar. And letting go, it turns out, is a brutal kind of devotion. Not dramatic or cinematic—just quietly, persistently painful. And so this wasn’t the kind of letting go that makes a loud exit. It was quiet, atmospheric. A slow disintegration of certainty. Writing stories, building imaginations word for word, was the oldest known form of creativity to me. And so ‘the essay’ was always there. Even when the documentary image carried more weight in my practice than the supporting text. But back then, the essay served mostly as support. It filled in, explained, expanded upon the visual. It moved alongside the work but didn’t necessarily shape its method. It was only later—through the long unlearning of what constitutes “documentation,” through the shock of discovering that time could be porous and form could be soft—that the essay began to take on a different shape. No longer a companion or an afterthought, it became the very field where the work lived and changed. Not documentation, but dwelling. Not proof, but presence. Not a statement, but an unfolding. Now, writing an essay is no longer about translating the visual into words. It is about tending to that which refuses to be translated. It is fieldwork not because it travels far, but because it stays—inside the ritual, inside the tension, inside the self. And this shift was not clean. It could not have been. It came with mourning: the loss of clarity, of the performance of “objectivity,” of the safety of form. But it also came with a new kind of fluency, one that moved at the pace of breath rather than publication. The process moved from documentation to something closer to encounter.

But even as the essays transformed—slowed down, softened, turned inwards—something else remained stubbornly rigid. The packaging. The need to name. To brand. To position. Something in me resisted. Or rather, something I’d internalized, something I couldn’t quite name at the time, kept pulling me back toward the surface. Toward clarity. Toward legibility. It happens even now. A relapse of sorts. Toward a version of “real” that is etched into me by years of working in media spaces shaped by Western logic. My career as a media development practitioner has been spent helping small, independent media outlets survive in a hostile landscape. Content diversification. Audience segmentation. Strategic framing. Revenue pipelines. All of it designed to help stories “cut through the noise.” And somewhere along the way, I began to turn those same tools on myself. I couldn’t see the work unless I could frame it. I couldn’t feel its weight unless I could explain it—name it, brand it, position it. I had unknowingly become fluent in the very grammar that made it impossible to speak from within my own center. Under the guise of professionalism and creating real world knowledge, how deeply this colonial conditioning had (has) convinced us that stories only mattered when they were made palatable to a certainaudience, branded according to a certain method, and made all too easily consumable. This was the other major unsettling after the fellowship in December 2023. And it also just so happened, that this fellowship about photojournalism came to me at the same time when the myth of Western liberal media ruptured slowly, and then all at once as the war on Palestine laid bare the violent limits of objectivity, neutrality and progress. I, too, had been upholding the scaffolding. To this day I find myself trying to make something sacred bend to the rules of ‘realness’ and visibility. And so the tension grew. This project, this collection of essays and portraits and collages that use AI to build dreamworlds, this archive-in-the-making—refused to be named in the ways I had been trained to name. It wasn’t born out of clarity. It came as a haunting. The first time I departed from the working title of ‘A World Unseen’ happened at Mochi Gate in Muharram of 2024. If you are familiar with my short essay titled The Jinns of Mochi you will understand why I say it came as a haunting.

I was standing on the same balcony of the same Imam Bargah in the Kashmiri Mohalla where thousands of Muslims converge every year on the eve of Ashura to commemorate the moment before the moment, the final dawn before the battle of Karbala begins. This is done so through a very unique azaan (call to prayer) for Fajr. As soon as the azaan is called, there is ritual matam and zanjeer-zani. The world erupts through this rare, piercing azaan followed instantly by the eruption of matam, zanjeer-zani, a collective cry that tears through the dark. It is not just a remembrance. It is a summoning. That morning, as I stood there—sleepless, breath held, eyes scanning a crowd that already knew what was coming—I realized what it meant to invoke the heavens. What it means to say Karbala is not history, but Karbala Mualla: Karbala, the exalted. Karbala, a piece of heaven. And so even here—at a balcony above Mochi Gate, in this bruised and overburdened city—a place so far from the banks of the Euphrates, Karbala is not merely remembered. It is invoked. What is lost is not simply mourned. But called forth is what which remains Eternal. Through the ritual act—through breath and blood and rhythm—heaven is summoned into the streets. That was the moment the project found its name, then. Invoking the Heavens. But even Invoking the Heavens began to feel like only a partial truth. A thread, not the tapestry. As the worlds I was witnessing—dreamt, ritualized, lived—began to multiply, I found myself up against the limits of language again. Because what I was encountering could not be contained by invocation alone. These were not only glimpses of divinity or rupture through ritual. They were entire cosmologies, emerging in fragments, folding into each other. Worlds breaking open inside the present. Worlds refusing to stay buried. Part of it was also the perpetual self-surveillance.

And it was then, in sitting with the impossibility of naming, that another horizon revealed itself. I began thinking of the idea of the worlds to come not just as metaphor, but as method. As something real, already arriving. What is the return of the Imam if not the ultimate arrival of another world? What is a dream, if not a world that insists on its own reality? A miracle—a world to come. A rupture in logic—also a world to come. Each encounter, each transmission, each glitch in the fabric of the everyday, announcing that something else is possible. That the veil is thinner than we think. These worlds do not exist somewhere else. They are not deferred. They bleed—sometimes quite literally—into the here and now. My work is full of blood because blood is the motif that reminds us that the sacred is not sterile. It is not abstract. It stains. It spills. It insists on being remembered.

And so it became clear: the essay, too, had to evolve. It could no longer function as a vessel of neat conclusions or retrospective coherence. It had to hold the same multiplicity, the same porousness, that I was encountering in ritual, in memory, in dreams. If fieldwork is a mode of presence, of attention, of immersion, then this—this writing—was my fieldwork. Because to write this way is to be in the field—not of anthropology, but of inheritance. Not of method, but of intuition. Not to know, but to stay. To stay with the tremble. To stay with the not-yet. To stay with what still asks to be believed. This essay is not about the worlds to come – it is one.

Leave a Reply